Automatic language translation

Our website uses an automatic service to translate our content into different languages. These translations should be used as a guide only. See our Accessibility page for further information.

Issued: 15 March 2019

Northern Territory v Griffiths (Deceased) on behalf of the Ngaliwurru and Nungali Peoples [2019] HCA 7 is the first time the High Court of Australia has considered how to calculate the compensation owed to native title holders for acts that affect the enjoyment of their rights and interests.

This decision provides important guidance for NSW Government agencies regarding how compensation for acts affecting native title, including future acts, will be calculated.

The Ngaliwurru and Nungali peoples, who hold native title to land at Timber Creek in the Northern Territory, claimed compensation under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) for various grants and public works that affected their enjoyment of that title.

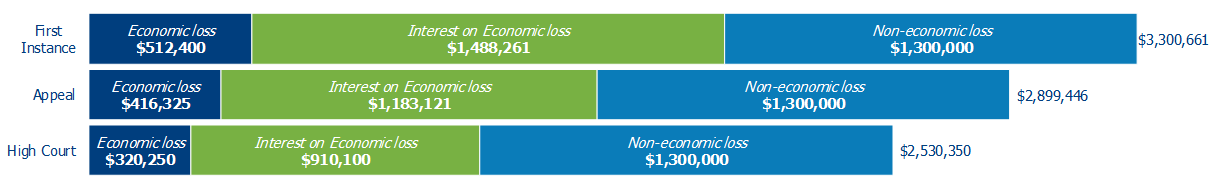

In 2016, the Federal Court awarded the native title holders $3,300,661 in compensation (see Griffiths v Northern Territory [2016] FCA 900). That amount consisted of: $512,400 for economic loss; $1,488,261 in interest, calculated on a simple basis, on that loss; and $1,300,000 for intangible damages resulting from the extinguishment of native title. The quantum of economic loss was calculated on the basis that the value of non-exclusive native title held by the Ngaliwurru and Nungali was equivalent to 80% of the economic value of a freehold to the land. The intangible damages were essentially intuitively calculated.

In 2017, the Full Court confirmed that interest was to be calculated on a simple basis and affirmed the award for intangible damages (see Griffiths v Northern Territory [2017] FCAFC 106). However, the Full Court held that the first instance court had overvalued the non-exclusive native title. The Full Court held that non-exclusive native title was to be valued at 65% of the value of the freehold. On that basis, the compensation award was reduced to $2,899,446 with a commensurate reduction in the interest awarded.

On appeal to the High Court, there were three key issues.

The first issue on appeal was how to ascertain the economic value of the affected native title.

The High Court accepted that it was appropriate to distinguish between (i) determining the economic value of the native title affected by an act, and (ii) estimating the loss arising from any diminution of the native title holders' connection to country (at [84]). The second of these was considered in the context of determining compensation for loss of connection.

The High Court held that:

The High Court affirmed that, where some native title rights and interests are affected, the correct approach is to (i) determine the value of a freehold interest to the land and (ii) discount that figure by reference to the nature of the native title rights and interests affected. Here, since the native title holders only held non-exclusive native title, the economic value of their rights and interests was held to be 50% of the freehold value. This conclusion is significant because it is considerably less than the 80% found at first instance.

While the High Court noted that there was an element of artifice to this approach, it accepted the parties adoption of the "Spencer test" – what a reasonable purchaser desiring to buy the land would have had to pay a vendor willing, but not anxious, to sell it for a fair price (see Spencer v Commonwealth (1907) 5 CLR 418) – when determining the economic value of native title (at [85]).

The High Court's determination of this issue provides NSW government agencies with clear guidance on how to ascertain the economic value of native title. Usefully, the approach of equating the native title interest affected to a percentage of the value of the freehold seems open to adaptation to the calculation of compensation for future acts, such as the acquisition of easements or the grant of licences, that impair the enjoyment of native title.

The second issue was whether interest on the compensation for economic loss was to be calculated on a simple or a compound basis.

The native title holders had contended that interest should have been calculated on a compound basis.

The High Court affirmed that interest should be calculated on a simple basis (at [109]). The Court left open the possibility that interest could be claimed on a compound basis, but held that the native title holders had not properly made such a claim (at [133]).

The detailed consideration of the native title holders' arguments may provide guidance to future compensation claimants as to how to claim compound interest. However, there appear to be significant evidentiary hurdles for such a claim.

The third issue was how the extinguishment of native title holders' connection to country is to be reflected in compensation.

The High Court, holding that compensation for loss or diminution of traditional attachment, or spiritual connection, to the land is the amount that society would rightly regard as an appropriate award, affirmed the first instance award of $1.3 million.

So doing, the High Court observed that the first instance judge had had the benefit of evidence from the native title holders regarding (i) the effect, under traditional laws and customs, of when country is harmed, and (ii) the effects of the acts on their connection to and relationship with country (at [236]). These effects were to be viewed not in isolation but by reference to the whole area in which the native title holders held rights and interests (at [219]).

Significantly, the High Court's emphasis on the native title holders' evidence of the effect of the compensable acts on their connection indicates an onus to be satisfied in compensation claims. Given the courts' detailed analysis of the evidence, it seems that it will not be sufficient for native title holders to merely assert that their connection has been affected and claim compensation for that diminution at large. Where a claim is made with supporting evidence, it can be assessed by reference to whether it is appropriate, fair or just. What factors may be relevant to that assessment remain to be developed.

Further, the High Court warned against over reliance on State compulsory acquisition laws when determining the non-economic component of native title compensation. The Court stressed that while legislation like the Land Acquisition (Just Terms Compensation) Act 1991 (NSW) can inform the calculation of compensation, it is not determinative.

The Crown Solicitor can advise you on any questions that arise from the High Court's decision, and specifically on any native title issues that arise in the context of NSW Government development projects and property transactions.

Jodi Denehy, Director

jodi.denehy@cso.nsw.gov.au

02 9474 9454

Janet Moss, Principal Solicitor

janet.moss@cso.nsw.gov.au

02 9474 9254

Martin Hill, Principal Solicitor

martin.hill@cso.nsw.gov.au

02 9474 9074

To subscribe to legal alerts, email the CSO Marketing and Communications team at: csomarketing@cso.nsw.gov.au.

Last updated: